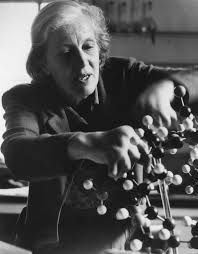

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin was a pioneering British chemist, who was awarded a Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964 for the determination of the structures of penicillin and vitamin B12.

THERE WAS MAGIC ABOUT HER PERSON

Dorothy was born in Cairo on 12 May 1910, to parents involved in the colonial administration of countries in North Africa and the Middle East. Although she was sent to a local school in England under the charge of her grandparents, it was her mother who encouraged her love of science. For Dorothy’s sixteenth birthday, her mother gave her a book on crystallography, the specialism she would go on to develop. When later asked to name her heroes, she would cite the medical missionary Mary Slessor, Margery Fry, the Principal of Somerville College, and, above all others, her mother.

Dorothy fought to be allowed to study science with another girl at the school, and in 1928 was awarded a place to read chemistry at Somerville College, one of the first two women’s colleges in Oxford. Having not studied the Latin required for the Oxbridge entrance exam, her headmaster privately tutored her.

In 1932, Dorothy graduated with a first-class degree from Oxford, the third woman to ever do so.

a brilliant mind and an iron will to succeed

After her graduation, Dorothy moved to Cambridge to undertake doctoral research on pepsin. She returned to Somerville College in 1934 and remained there until her retirement in 1977. After establishing an X-ray laboratory in the Natural History Museum, she began work on determining the structure of insulin.

In 1939, she was asked to solve the structure of penicillin by the Australian pathologist Howard Florey. By 1945 she had succeeded in describing in three dimensions the arrangement of its atoms, which led to her election to the Royal Society in 1947. She went on to discover the structure of vitamin B12 in the mid-1950s, leading to her election in 1960 as the first Wolfson Research Professor of the Royal Society.

Dorothy finally won the Nobel Prize in 1964 for her work on penicillin and vitamin B12, after being nominated multiple times. The following year she was made a member of the Order of Merit, Britain’s highest honour for achievement in science, the arts and public life. She was the second woman to do so, preceded only by Florence Nightingale.

In 1969, she finally cracked the structure of insulin, 34 years after she had taken her first X-ray image.

SHE RADIATED LOVE

Dorothy devoted much of her life to encouraging and supporting the work of scientists in developing countries. She had acquired from her mother a concern for social inequalities, and developed a particular concern for the threat of nuclear war. In 1976, she became president of the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, stepping down in 1988, the year after the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty imposed a global ban on short- and long-range nuclear weapons systems.

Dorothy retired from public life in 1988, although she made it to the 1993 International Union of Crystallography Congress in Beijing, aged 83. Dorothy died on 29 July 1994.